让从旅途中归来的兄弟……寻求所有人为他们的过失祈祷……他们中的任何一个人都不要擅自将自己在修道院外看到或听到的任何事情告诉别人,因为这会让人分心。——《圣本笃规则》,第 67 章

乍一看,修道院呼吁脱离世俗世界似乎让修道院僧侣们对公共生活和为更广泛的社区服务兴趣不大。然而,修道院是经济生产的巨大引擎,可以改良土地、培育更好的牲畜和农作物,并复制稀缺的书籍。他们与周边社区进行贸易,僧侣越来越多地被招募来履行公民职责——他们识字,被认为在司法和政治问题上比当地绅士更公正。修道院的退隐通常会培养出在地方、国家甚至国际舞台上崭露头角的领导人。

热情好客

其中有两位领导人,也是西方众多修道院领袖中的两位,可以说明这种矛盾,他们是:努尔西亚的本笃(约 480-547 年)和宣传本笃生平事迹的教皇格里高利一世“大帝”(约 540-604 年)。

本笃十六世是意大利北部努西亚一个罗马贵族家庭的儿子;他大约 20 岁时前往罗马学习,但很快感到不满并离开了。在隐居一段时间后,他又担任了苏比亚科附近一座已存在的修道院的院长,但未能成功,之后他开始建立自己的修道院——总共 13 座,最后一座是罗马附近著名的蒙特卡西诺修道院。本笃十六世为蒙特卡西诺撰写了至今仍统治着本笃会的规则。

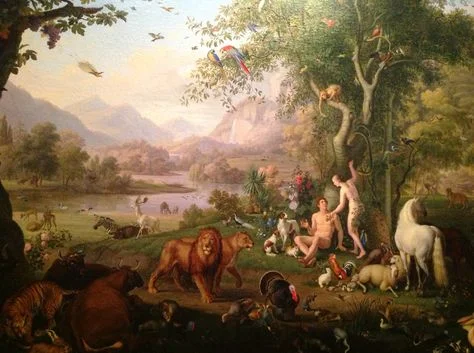

在本笃十六世的愿景中(在他的规则序言中表达),社区是一所“为主服务的学校”,一个“我们希望建立的制度不会苛刻,也不会繁重”。尽管本笃十六世强调放弃世俗追求并致力于精神工作,但他也提倡对外来者热情好客。规则为外来者的到来做了安排:“让所有碰巧来的客人都受到基督般的接待。”为客人和穷人服务是修道院生活的重要组成部分(有关规则的更多详细信息,请参阅第 15 页)。

One reason we know as much as we do about Benedict is that his faithful life caught the attention of Gregory. Gregory is known for a number of important commentaries, sermons, and letters, but also for the Dialogues, four books on holy men of the sixth century and the various miracles, signs, and healings they had performed. In the Second Book of Dialogues, Gregory praises Benedict as a hero and portrays him predominately as a miracle worker.

These miracle stories focus not only on Benedict’s personal piety, or even on his skills as a practical organizer and spiritual father of his community as seen in the Rule. Rather, Gregory told of miracles of Benedict that helped and healed those in his monastic and wider community. Gregory focused also on Benedict’s relief of poverty and hardship, with tales of how he brought water from a rock, revived the sick, paid the debts of the poor, and filled an empty barrel with oil. While most monks could not expect to perform such miracles, all could expect to be guided by Benedict’s example in their daily civic engagement.

Refocusing on the poor

Gregory’s own life demonstrated the same tension and rhythm between monastic life and the wider community. Gregory’s family background was similar to Benedict’s. He was born Gregorius Anicius to a wealthy Roman noble family in a villa on the Caelian Hill, one of the famous seven hills of Rome, and raised in a period of distress—during the Plague of Justinian in the mid-540s, a pandemic that killed about a fifth of the city’s population. Famine and political unrest were also common.

Gregory’s father, Gordianus, a prominent political and church administrator, influenced his son’s future trajectory. (Gordianus may have been the great-grandson of Pope Felix III, and Gregory’s mother, Silvia, was well-born.) Gregory became an urban prefect of Rome at the age of 30, showing early a talent for administration that would serve him well throughout his life.

After his father’s death, around 574 Gregory transformed his family villa into an urban-based monastery called Saint Andrew’s, balancing his desire for contemplation with his public duty to serve others. In 579 Pope Pelagius II ordained Gregory a deacon and sent him to Constantinople as ambassador to the imperial court. Pelagius tasked Gregory to get help from the emperor so that Rome could fend off the attacking Lombards, but Gregory was not successful. After returning to Rome, Gregory was elected pope by acclamation in 590 after Pelagius II died of yet another plague.

As pope, Gregory faced a number of challenges, including continuing to defend Rome against outside aggression. In the absence of secular leadership that encouraged peace, a major feat of Gregory’s papacy was the way he calmed the political instability and stabilized the city’s economy.

格雷戈里在稳定了局势后,便开始专注于教会的工作。长期的瘟疫、饥荒和战争导致大量难民涌入城市,许多人陷入贫困。在没有其他领导人的情况下,格雷戈里让教会开始工作。

自使徒时代以来,基督徒就一直接受捐赠以分发给穷人(例如,参见罗马书 15:25-31)。然而,当格雷戈里成为教皇时,教会和国家的扶贫计划无法满足这一任务的规模。格雷戈里建立了一套跟踪捐赠的系统,鼓励教会领袖寻找有需要的人,并加大教会土地上粮食的生产。他帮助穷人的能力使他在城市人口中建立了声誉,巩固了他的遗产。

他的工作重点不仅在罗马,他还重组了北部和西部非基督教部落的教会传教工作。在一项现在被称为格里高利传教团的计划中,他派遣当时担任圣安德鲁修道院院长的坎特伯雷的奥古斯丁 (d. 604) 去英格兰向盎格鲁撒克逊人传教。

格里高利对公民参与的理解不仅受到他作为行政官的经历的影响,还受到他的修道院承诺的影响。即使在担任教皇行政官和教皇期间,格里高利的生活和工作也受到修道院节奏的组织。他对修道院生活和扶贫的兴趣也体现在《本笃十六世传》等著作中。

新的本笃

新的本笃

随着修道制度的发展,出现了新的奉献生活类型(见第 46-47 页),在某些情况下,这些生活完全致力于“为世界”服务 – 特别是在学校、医院以及致力于帮助穷人的组织,如孤儿院和食品厨房。

尽管新教改革者正式拒绝修道主义,但他们仍继续阅读许多修道院作家的作品。在二十世纪,新教修道院生活受到启发的例子包括法国的泰泽和德国的芬肯瓦尔德(见第 42-44 页)。

苏格兰裔美国哲学家阿利斯代尔·麦金太尔(Alisdair MacIntyre)在其著名的《追求美德》(1981)一书中,呼吁建立地方修道院式社区:

……文明、知识和道德生活得以在已经来临的新黑暗时代中得以维持。如果美德传统能够经受住上一个黑暗时代的恐怖,我们并非完全没有希望。但这一次,野蛮人并没有在边界之外等待;他们已经统治我们很长一段时间了。我们之所以陷入困境,部分原因在于我们对此缺乏认识。我们等待的不是戈多(指塞缪尔·贝克特的 戏剧《等待戈多》),而是另一个——无疑截然不同的——圣本笃。

基督徒用麦金太尔的话来支持截然不同的公民参与模式,从 21 世纪初的“新修道主义”运动到罗德·德雷尔的《本笃选择》(2017 年)。他们认为,修道主义是动荡的中世纪早期维持教会和社会的关键,在他们看来,那是一个经过实践检验的忠实的基督教公民参与方法。

“黑暗时代”这个概念本身就存在问题,更不用说与当代社会或政治相比了。然而,更好地理解修道院传统中的公民参与仍然具有启示意义。修道院传统在最好的情况下,不是躲避世界,而是为世界祈祷、管理世界、教导世界、照料世界、书写世界、向世界传福音、供养世界、与世界交易、欢迎世界客人。CH

杰森·祖德玛

[本文最初发表于《基督教历史》2021 年第 141 期]

杰森·祖德玛 (Jason Zuidema) 是《理解加拿大的奉献生活:当代趋势评论论文》的编辑,也是北美海事部协会的执行董事。

原文出处:https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/prayer-provision-service-ch-141